I recently attended a talk by Alvis Brazma that contained a little bit of everything including John von Neumann’s self-replicating machines and ChatGPT. This together with recently stumbling across a preprint about how training ChatGPT on itself causes a model collapse led to the following line of thought on how self-replicating machines are connected to large language models (LLMs) and what, if any, consequences that has on the discussion around LLMs and artificial general intelligence.

What’s a self-replicating machine

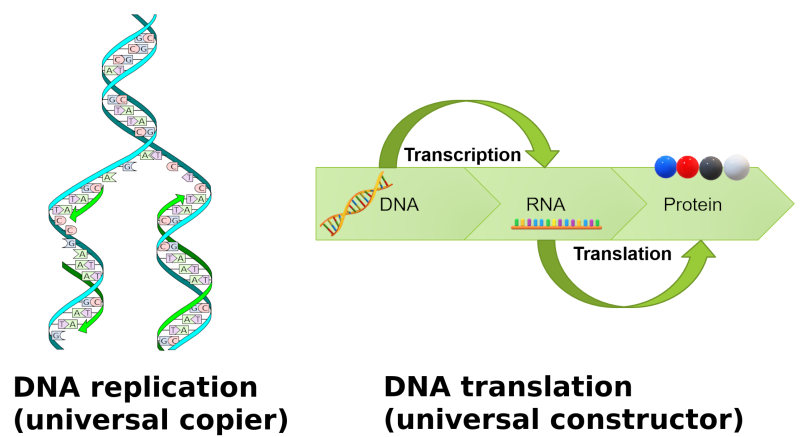

Self-replicating machines, or replicators, are autonomous constructs that have the ability to produce copies of themselves. The replication process itself happens through a universal constructor that produces a copy of the machine based on a blueprint while a separate copy process, a universal copier, produces a copy of the blueprint. Together these copies of the machine and its blueprint constitute a fully functional replicate of the original.

Perhaps somewhat unintuitively, the universal copier and constructor are separate processes. There is a good reason for the separation as it turns out to be a necessary condition for enabling evolution of the replicators through accumulation of changes in the blueprint. In this framework the essential replication machinery maintains its integrity over generations but changes are permitted in other functions the machine might serve.

DNA replication and translation correspond to a self-replicating machine.

One famous example of self-replicating machine is found in DNA-based biological organisms, where DNA replication and translation follow the same separation of responsibilities. Any other functions falling outside the realm of replication and translation are assigned the set of unrelated operations, which may be adapted to improve the organism’s survival in different environments while preserving the continuation of the replication chain.

LLMs as replicators

While an LLM might not seem like a replicator at first, we can impose the same framework on them by starting with assigning the role of the blueprint to the input data the model was trained on. The training data is essentially an instruction set that – when translated by a computer program – contains the necessary information to reconstruct the LLM, the data to me seems to fulfill the function of a blueprint. Immediately from this assignment it follows that the universal constructor is the set of code that needs to be executed to infer the LLM from the training data.

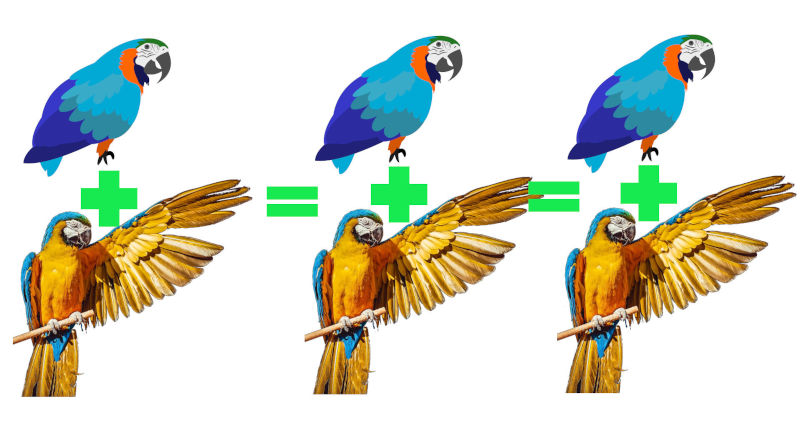

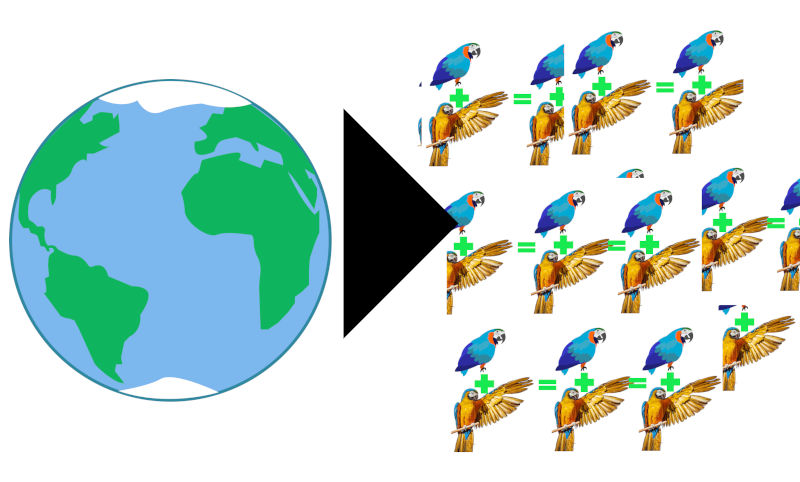

Responsible machine learners feed their models with organic human data.

However, LLMs do not contain the full training data but rather some low-dimensional representation that somehow mimics its characteristics, there is at first no clear candidate for the role of the universal copier. Instead, what can be done is to query the LLM itself for a set of training data and then use that data in creating the next replicator generation. Apart from limited AWS credits and a little voice of sanity in the back of our heads stopping us, there should in principle be nothing stopping us from repeating this process as many times as we wish.

But does defining the universal copier as queries to the LLM replicate the training data with sufficient accuracy to keep the self-replication machinery intact over subsequent generations?

Degradation and collapse

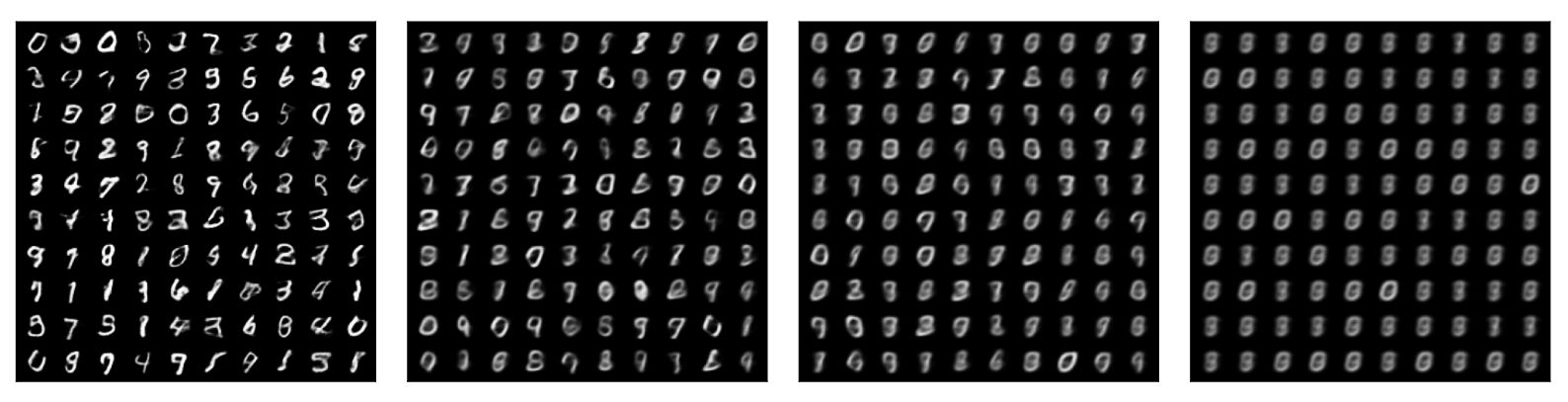

Recently, Shumailov et al. demonstrated that for Gaussian mixture models, variational autoencoders, and LLMs using data generated from these models to retrain a new generation of the same model results in convergence to a state where outputs from the final generations consist of a single point. This phenomenon is called model collapse and manifests as a loss of complexity (variance) in the outputs. According to Shumailov et al., model collapse affects a wide range of generative models and, crucially, also the state-of-the-art LLMs such as the various generations of ChatGPT.

Training generations of variational autoencoders on the previous generations' outputs causes a model collapse that manifests as a unimodal distribution. Modified from Figure 9 in Shumailov et al.

Model collapse has significant ramifications for our formulation of LLMs as self-replicating machines. With each generation, the ability of the model to produce accurate training data gets worse, and a core part of the replication machinery, the universal copier, is compromised more and more by inclusion of LLM-generated content in the training data. This means that the further the LLMs evolve in this manner, the worse their ability to produce a high-quality blueprint becomes. Over time, the changes accumulate enough that an eventual and unavoidable collapse to happens, and outputs from the LLM start to consist of repeated phrases . – much like a parrot repeating its phrases in mimicry of human language stochastic parrots.

One might be inclined to suggest that model collapse can be avoided by carrying over a copy of the original training data. While this would preserve the ability of the model to produce exact copies of itself, the replicator would lose its capability to improve or evolve over time. Although fine for simply considering the model as an useful tool trained on a snapshot in time, the model would lose its ability to explain events that happened after its training data was collected.

The next immediate solution is to only train on human-generated inputs and exclude any inputs generated from the previous generation of the LLM in training of the next. Unfortunately as the flood of LLM-generated content inevitably floods large parts of virtual public spaces, exclusion of LLM-content will become increasingly challenging and eventually infeasible.

The root cause of these issues is, of course, that LLMs do not truly understand the languages they are modelling and merely chain words together in a manner that is satisfactory to a human observer. Some might argue that this is not truly a problem and, since language models already can or eventually will pass the fabled Turing test (which itself is not a good measure of artificial intelligence)[]), we should just trust the LLMs to curate the data for us and even start considering them as artificial intelligences with emergent behaviour.

Why LLMs aren’t AGIs in this framework

Obviously, LLMs are not artificial general intelligences and, unlike some tech evangelists like to preach, there is no imminent threat of an AI apocalypse initiated by a ChatGPT instance radicalized by reading too many young adult novel fanfics. Because this post is about the connection between self-replicating machines and not about end-of-the-world scenarios, I’ll make one more reaching conclusion in how the lack of artificial intelligence in LLMs might be connected to degradation in the universal copier.

The earth probably won’t be converted into a writhing mass of stochastic parrots in a gray goo scenario initiated by a fed up ChatGPT.

A defining feature of artificial general intelligence is its ability to think and learn, or have a consciousness in a manner similar to ours. It stands to reason that a machine that we accept as artificial intelligence would also be interested in its continued survival through self-propagation independently of human input. Thus I, not being a philosopher, would go as far as saying that the definition of a general AI should include either the capability to acquire or established presence of functional self-replication machinery. As demonstrated by this post and the experiences of anyone using LLMs, these models are currently nowhere near that state and are probably a dead-end as far as artificial general intelligence is concerned.

What I think this all means

LLMs are and will likely remain what they are today: a useful tool taking the form of an interactive search engine. No doubt general availability of models capable of digesting an internet’s worth of information will have a similar influence on the internet as the general availability of dumb search engines once did. Eventually, if a singularity of human self-reflection is reached perhaps with a little help from LLMs, the CEO grifters advertising AI doomsday in hopes of attracting investment may even come to admit that their AI doomsday scenario was mostly about preventing their competitors accessing the same research and resources they’ve already acquired through virtue of being the first in the field to do so.